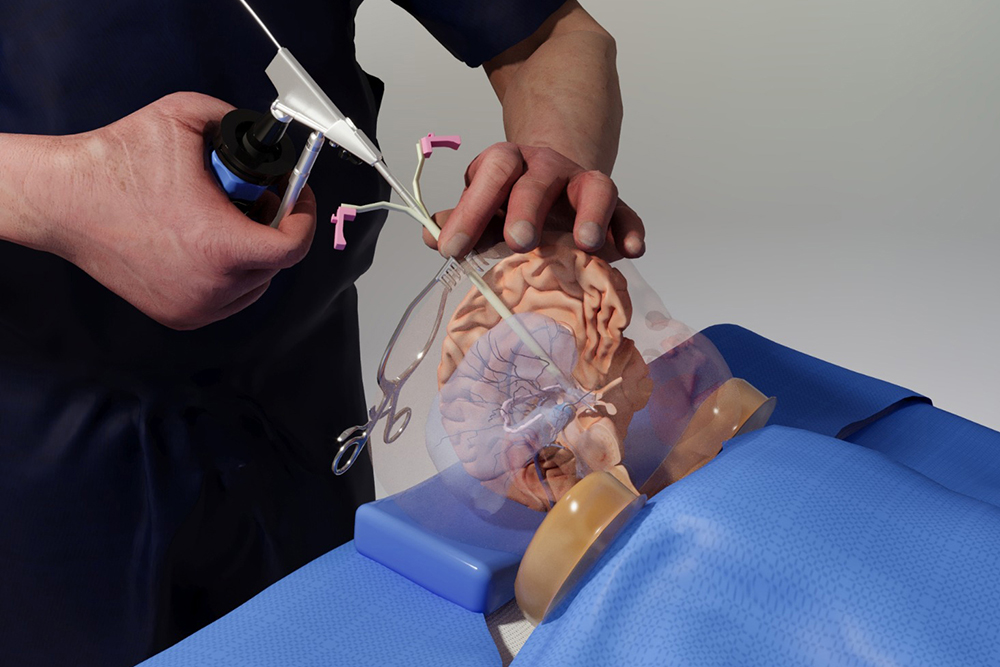

Benjamin Wharf, a renowned neurosurgeon at Boston Children’s Hospital, works in the MIT.nano Immersion Lab. More than 3,000 miles away, his virtual avatar stands next to Matheus Vasconcelos in Brazil as the resident performs delicate surgery on a doll-like model of a child’s brain.

With a pair of virtual-reality goggles, Vasconcelos is able to see Warf’s avatar performing the brain surgery procedure before mimicking the technique and asking questions of Warf’s digital twin.

“It’s almost an out-of-body experience,” Warf says of watching his avatar interact with residents. “Maybe this is what it feels like to have an identical twin?”

And that’s the goal: Worf’s digital twin bridges the distance, allowing him to functionally be in two places at the same time. “This was my first training using this model, and its performance was excellent,” says Vasconcelos, a neurosurgery resident at the Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medical Sciences in São Paulo, Brazil. “As a resident, I now feel more confident and comfortable applying techniques to a real patient under the guidance of a professor.”

Worf’s incarnation came to life via a new project launched by medical simulator and augmented reality (AR) company EDUCSIM. The company is part of START.nano’s 2023 cohort, MIT.nano’s deep-tech accelerator that provides early-stage startups with discounted access to MIT.nano’s labs.

In March 2023, Giselle Coelho, scientific director of EDUCSIM and pediatric neurosurgeon at Santa Casa de São Paulo and Sabara Children’s Hospital, began working with technical staff at the MIT.nano Immersion Lab to create an avatar of Warf. By November, Avtar was training future surgeons like Vasconcelos.

Coelho says, “I came up with the idea of creating an avatar of Dr. Worf as a proof of concept and I asked, ‘Where in the world would be the place where they’re working on these kinds of technologies?’ “Then I found MIT.nano.”

catching a surgeon

As a neurosurgery resident, Coelho was so frustrated by the lack of practical training options for complex surgeries that she created her own model of a child’s brain. The physical model includes all the structures of the brain and can even simulate a hemorrhage, “simulating all the steps of surgery from making the incision to closing the skin,” she says.

She soon found that simulators and virtual reality (VR) demonstrations eased the learning curve for her own residents. Coelho launched EDUCSIM in 2017 to expand the diversity and accessibility of training for residents and specialists interested in learning new technology.

Those techniques include a procedure to treat infantile hydrocephalus that Wharf, director of neonatal and congenital neurosurgery at Boston Children’s Hospital, pioneered. Coelho had learned the technique directly from Warf and thought his incarnation could be a way for surgeons who could not travel to Boston to benefit from his expertise.

To create the avatar, Coelho worked with Talis Rex, an AR/VR/gaming/big data IT technologist at Immersion Labs.

“For startups, access to a lot of technology and hardware can be very expensive when starting their company’s journey,” explains Rex. “START.nano is a way to enable them to access and afford the tools and technologies found in MIT.nano’s Immersion Lab.”

Coelho and his colleagues required high-fidelity and high-resolution motion-capture technology, volumetric video capture, and a range of other VR/AR technologies to capture Warf’s skilled finger movements and facial expressions. Wharf visited MIT.nano on several occasions to digitally “capture” nanotechnology, including performing operations on physical infant models while wearing special gloves and clothing fitted with sensors.

“These technologies are mostly used for entertainment or VFX (visual effects) or CGI (computer generated imagery),” Rex says, “but this is a unique project, because we can now use it for real medical practice and real learning.” Are implementing. ,

Rex says one of the biggest challenges was helping to develop what Coelho calls “holoportation” – broadcasting 3D, volumetric video captures of Worf in real time over the Internet so that his avatar could be used in intercontinental medical training. Can be seen.

Warf Avatar has synchronous and asynchronous modes. The training Vasconcelos received was in asynchronous mode, where residents could watch the avatar’s demonstrations and ask him questions. The answers, provided in different languages, come from AI algorithms that draw from previous research and an extensive bank of questions and answers provided by Warf.

In synchronous mode, Warf operates his avatar remotely in real time, says Coelho. “He could walk around the room, he could talk to me, he could guide me. It’s amazing.”

Coelho, Warf, Rex and other members of the team demonstrated the combination of modes in the second session in late December. This demo included volumetric live video capture between the Immersion Lab and Brazil, spatialized and visible in real time through an AR headset. This was significantly expanded compared to the previous demo, in which volumetric data was streamed in only one direction through a two-dimensional display.

powerful effect

Whorf has a long history of training desperately needed pediatric neurosurgeons around the world, most recently through his nonprofit NeuroKids. He says remote and simulated training has been a large part of training since the pandemic, though he doesn’t think it will ever completely replace in-person hands-on instruction and collaboration.

“But if one day we actually have avatars, like this avatar of Gisele, showing people in remote places how to do things and answering their questions, without the cost of travel, without the cost of time, etc. “Could be really powerful,” I think, says Warf.

Coelho says the Avatar project is especially important for surgeons serving remote and underserved areas, such as Brazil’s Amazon region. “This is a way to give them the same level of education they would get at other places, and the same opportunity to stay in touch with Dr. Wharf.”

According to Coelho, a child recently treated for hydrocephalus at an Amazon clinic traveled 30 hours by boat for surgery.

Training surgeons with avatars, she says, “could change reality and change the future for this child.”